Veronika Gyòcsi Stenzel (1945, Budapest) was born a few months after the end of WWII and shortly before the onset of the Cold War, into a middle-class family. Her father, though never a Party member, was Chief Veterinarian of the Ministry of Agriculture of the young, socialist People’s Republic of Hungary. Both parents were active in the cultural and intellectual circles of Budapest, where a resistance of sorts was being played out by the members of the now despised bourgeoisie. Her lifelong love for classical music was established at an early age as she learned to play the piano and sing to entertain house guests and family friends, ultimately resulting in piano studies at the Budapest Conservatory under, among others, Zoltán Kodály, on track to becoming a concert pianist. Parallel to studies in music, Veronika Gyòcsi had also begun learning German and became proficient enough to work as a tour guide, a translator and interpreter, bringing her in contact with West German businessman, Günther Stenzel, whom she later married in 1967.

A year and several interrogations later, she moved to Vienna to be with her husband. For the first few years she struggled to acclimatise to life in a free society, where political, social and artistic debate were commonplace. It is likely that her love of nonconformist Soviet art, authentic expressions of critical thought and emotion in a climate of duress, began to take shape, now that she was living the great contrast herself.

György Marosvári, A View, 1976, Oil on Cardboard, 100 x 100 cm.

In the 1970s open-heart surgical technology arrived in the East from the US and as the Soviet Union was keen to update their own technology and improve their healthcare system, significant resources were made available for this purpose. In 1973 Veronika Gyòcsi began working as a freelancer for several companies that were based in the West by distributing their sterile single-use surgical tools in Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania and later in other Soviet Republics. She worked closely with experts to train local nurses, doctors and technicians in using the new equipment while organising visits for them to Austria, Germany, Denmark and the US to learn the latest surgical procedures first-hand. During her travels to the Soviet Union she began her foray into collecting, buying from local galleries, artists’ studios and street artists. She had not set out to become a collector – her systematic support of certain artists, relentless searching, commissioning of works and establishing long-lasting relations with artists came between the late 1970s and early 1980s. Her interest in art collecting initially was naive; she looked for paintings to hang at home in Vienna that connected her to old joys and current struggles of life in Hungary and elsewhere behind the Iron Curtain.

Gajzágó Sandor, The Whore of Babylon, c. 1978, Oil on canvas, 80 x 160 cm.

Soon after her entry into the industry she established lucrative East-West trade networks, eventually setting up her own company in the early 1980s and, as a medium-sized private business, actually benefiting from the centralized power structure of a nationalized economy, against the backdrop of Soviet ambitions to improve and modernize the healthcare system. Medical symposia, conferences and local schoolings became the order of the working day, involving trips to Denmark, Germany, the US and many parts of the Soviet Union. Glasnost (“Openness”) was instated only two months into Mikhail Gorbachev’s tenure, followed only a year later by Perestroika (“Restructuring”), a series of reforms passed in a desperate attempt to boost the stagnant Soviet economy. First proposed in 1986, Perestroika was intended to bring about limited private ownership through cooperative local business ventures, foreign investment and a controlled opening of the hitherto highly regulated market. By this time, Veronika Gyòcsi had long established a stable footing in her field and was one of only two female entrepreneurs playing the medical supplies field in the Soviet Union. As her company enjoyed great success, she was able to open offices in Moscow, Odessa and Tallinn and to collect more seriously and more regularly. Whereas trips to the Soviet Union had hitherto been work-related, she now began travelling with the sole purpose of discovering and purchasing art for her collection. Her business trips continued to be conducted in search of new clients, to secure deals and to represent her company at healthcare technology fairs, where traders and manufacturers from the West had the opportunity to showcase their products.

Biruta Delle, Nostalgia, 1988, Oil on canvas, 100 x 90 cm.

Two decades in the industry had brought Veronika Gyòcsi into contact with local doctors, mostly heart surgeons who were, like her, regulars at medical fairs and conferences, as well as art collectors in their own right. As they were more familiar with the local art scenes they offered her valuable insight and introduced her to several nonconformist artists whom she would otherwise not have known as a foreigner. Between paintings, heart monitors and business deals, these events also offered dissidents opportunities to look for help, among Western visitors, to escape the Soviet Union. As it was illegal to exit the Soviet Union with one’s personal documents, (i.e birth certificate, diplomas and so on), some doctors she had befriended entrusted her to move their documents out of the Soviet Union in preparation for their escape. In exchange, they paid her with works from their art collections, most of which were smuggled across the border.

In the late 1980s, the democratizing spirit of the revolution brought about a sense of euphoria, which spilt out across Czechoslovakia, the Baltic Republics and notably East Germany, where the Fall of the Berlin Wall represented the beginning of the end of the Soviet Regime and Bloc Economy. The uncertain political climate, as well as some social unrest, meant upheavals on the markets and existential struggles for small and medium-sized businesses still operating in the Soviet Union. Ironically, it was precisely the loosening of market controls which were to prove insurmountable for her business, as the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 ousted apparatchiks who had been Veronika Gyòcsi’s long-standing contacts and assistants. So Veronika Gyòcsi’s firm took a hit and had to be restructured to survive and in 1993 she relocated her business to Austria.

Jemal Kukhalashvili “Kouhala”, Birthday, 1991, Oil on canvas, 22 x 26 cm.

Democratic elections brought in new deputies and new ministers; foreign investment meant that market competition peaked for dominance in the medical supplies pond. Also, the social upheaval following the collapse of the Soviet Union meant that private business owners were often employing criminal means in order to prevail in a perilous struggle to the top. Whereas in the past a lone businesswoman crisscrossing the massive Soviet territories had been an unconventional sight, it was now dangerous to remain in the Soviet Union without an elaborate safety network. Despite the ground shifting beneath her, she continued to conduct several more projects from her new headquarters in Vienna. Probably the most remarkable of these was also to prove the final blow to her business, an annihilation executed in the unadulterated vein of the recently-ousted but not yet regenerated totalitarian mindset.

In 1996, Veronika Gyòcsi’s company received orders to organise and equip President Boris N. Yeltsin’s medical team so as to carry out his coronary bypass operation. Although the surgery was successful, the company’s proximity to and intimate knowledge of President Yeltsin’s health condition, coupled with close ties to US manufacturers, led to the Russian authorities becoming restless and expelling Veronika Gyòcsi from the country and banning her company from any further activity on Russian soil.

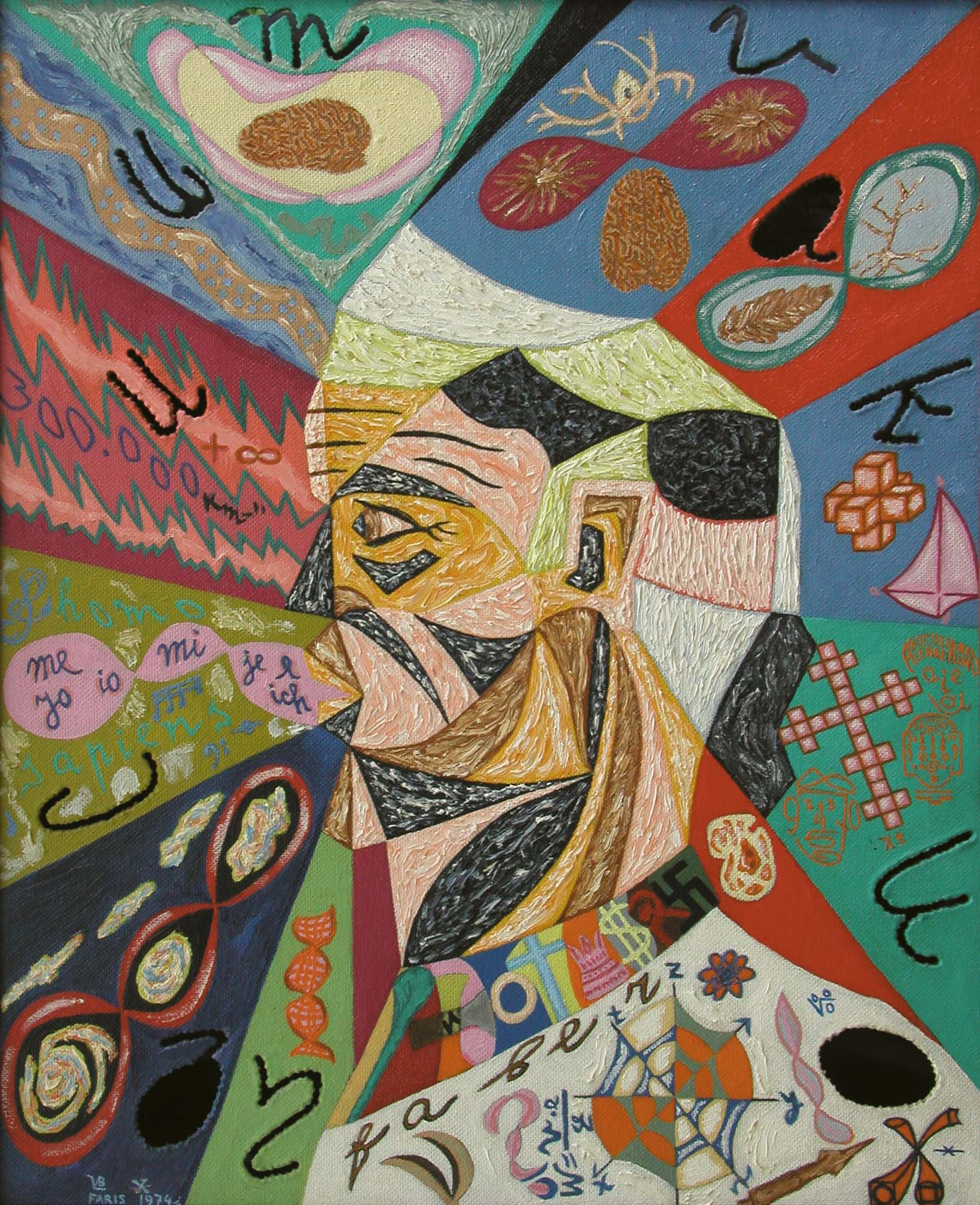

Unknown artist, signed “Vladimir Ivanovich Lebedev”, Faris, 1974, Oil on carton, 74 x 61 cm.

The final attempt at keeping her company afloat was made in 1997, when she oversaw the construction of a large-scale state of the art hospital in tentatively independent Ukraine. When rising tensions between the Russian Federation and its former satellite State led to the signing of The Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Partnership between them, Veronika Gyòcsi’s status as a trade associate of Ukraine became untenable. Again, in spite of the successful execution of the project, she was barred and her company never remunerated. This blow catalysed the company’s official bankruptcy a year later, bringing to an end this chapter of her life, and with it her collection of art works from the regions, which by now numbered close to four hundred pieces.

Veronika Gyòcsi, a child of the Soviet Era, cum Western entrepreneur, who built and lost a great life’s work operating on the borders between East and West when these territories were worlds apart, achieved much more than it could reasonably have been expected of an individual in these particular circumstances. Although bankrupt she walked away with an art collection that will serve as a historical document of one of the most defining moments of recent history. Though dormant for many years for lack of funds, attention to the collection has been restored as curators Denise Araouzou and Cory Scozzari lay the groundwork for a series of exhibitions, residencies and publications that attempt to contextualise the collection in the historic but also contemporary artistic landscapes of the countries represented within it. While acknowledging that the Communist system of government was beset by flaws, Veronika Gyòcsi recalls feeling a sense of community in her daily interactions with people that she has failed to find elsewhere since. She hopes one day to continue collecting.